Efficient Data Access with PIVOT

When following good database design principals, data is structured in some sort normalised form, usually Third normal form (3NF). Roughly, a table only contains columns that are all related to the primary key of the table. Usually in 3NF, a single piece of information is kept in exactly one place, which makes it easy to update and ensures consistency.

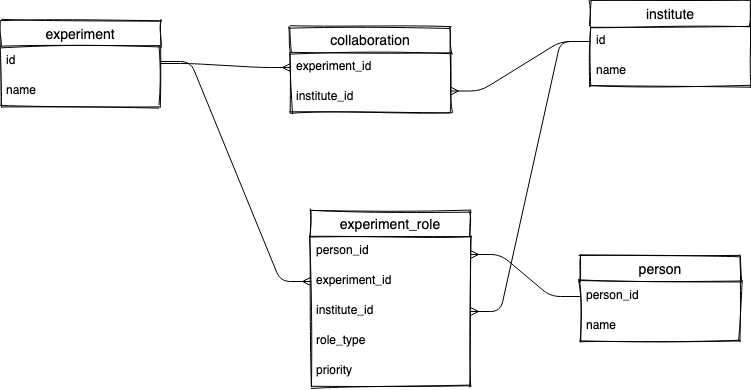

Consider this schema. Experiments and institutes are related via a collaboration. In addition, each collaboration may have people assigned to certain roles, e.g. Team Lead and Deputy Team Lead(s).

Generally a collaboration has a single team lead and 0-2 deputy team leads. The schema doesn’t enforce this, it’s just a business rule we know our data generally follows.

Data Access

A simple use case for this data structure would be to find all of the collaborations for a particular experiment, including the institute name and location

SELECT c.expcfcol as experiment_id,

e.txtcfexp as experiment_name,

c.inscfcol as institute_id,

i.or1cfins as institute_name,

i.placfins as institute_place

FROM foundation.cfcol c -- collaboration

JOIN foundation.cfins i ON c.inscfcol = i.codcfins -- institute

JOIN foundation.cfexp e ON c.expcfcol = e.namcfexp -- experiment

WHERE e.namcfexp = :exp

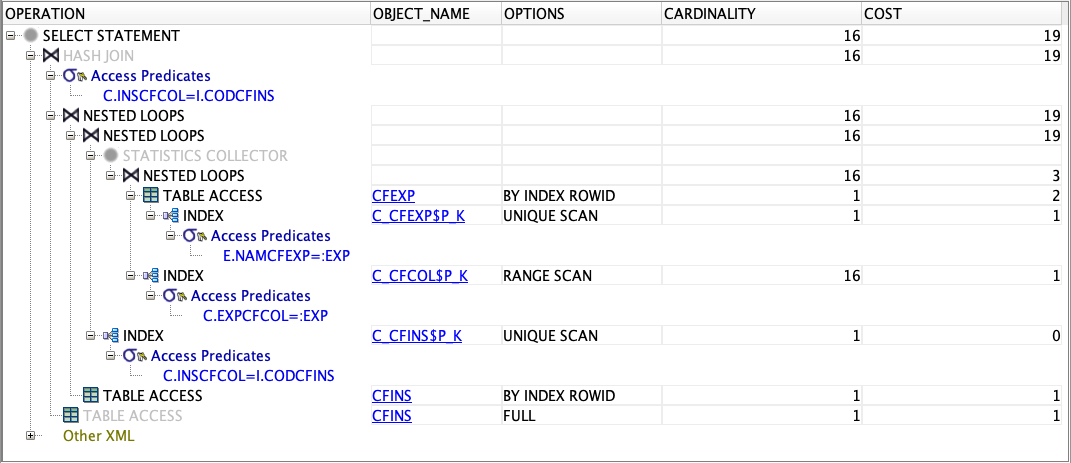

The query plan shows us a few options depending on which experiment is searched for. It all looks fairly efficient with indices being used. One interesting point, because we are referencing columns from the collaboration that are indexed foreign keys of the experiment and institute tables, there is no need to access the cfcol table, the indices and guarantees from the constraint is enough for the dbms to satisfy the query.

Another aside, the greyed out operations and the “statistics collector” operation indicate that the dbms will do some checks of the distribution of data based on the given parameters before deciding on the final plan. For example, if the experiment given has a lot of collaborations, it may decide to do a full table access of cfins and use a hash join instead of using a nested loop join and the institute index. This is why it’s important to use query params e.g. :exp when generating the query plan as the results may be different if you use a literal value e.g. ‘ATLAS’. The Autotrace feature can be helpful in telling you what plan was actually used for a query, along with other interesting statistics.

Denormalised Data Access

In the above query, the relations are fairly simple 1-1. We expect that there is a single experiment, institute pair, which can be enforced by a unique constrain on in the collaboration table. The person relation is a 1 to many relation. Each collaboration can have multiple people assigned with different roles.

Imagine we want to show the team lead and deputy team lead(s) of the collaboration as well as the other details. We will need to join on the role and person tables, including only the TL and DTL roles. For simplicity we’re doing an inner join, so collaborations without at least one TL or DTL will be excluded…

SELECT c.expcfcol as experiment_id,

e.txtcfexp as experiment_name,

c.inscfcol as institute_id,

i.or1cfins as institute_name,

i.placfins as institute_place,

p.namcfper as person_name,

er.role_type,

er.priority

FROM foundation.cfcol c

JOIN foundation.cfins i ON c.inscfcol = i.codcfins

JOIN foundation.cfexp e ON c.expcfcol = e.namcfexp

JOIN foundation.expanded_roles er on er.entity1_id = c.expcfcol and er.entity1_type = 'EXPERIMENT'

AND er.entity2_id = c.inscfcol and er.entity2_type = 'INSTITUTE'

JOIN foundation.cfper p on er.person_id = p.pidcfper

WHERE er.role_type in ('TL', 'DTL')

and e.namcfexp = :exp

The plan for this query starts to get a bit complicated but it’s still fairly efficient. Indexes are used and each table is accessed at most once.

Because of the 1 to many relation, we will get one row for each person that has a role for the collaboration, with the experiment and institute data being repeated for each row. This result format is rather inconvenient to display in a table, we only want 1 row per collaboration like before, but now we have up to 3!

Instead, we want a single row for each collaboration with 3 extra columns, teamlead_name, dtl1_name, dtl2_name. These columns contain will contain the name of the person holding the role for the collaboration or null if there is no one.

Using the tools we’ve already used, we might try to solve this problem with joins by joining on the role table for each role we are interested in.

SELECT c.expcfcol as experiment_id,

e.txtcfexp as experiment_name,

c.inscfcol as institute_id,

i.or1cfins as institute_name,

i.placfins as institute_place,

ptl.namcfper as teamlead_name,

pdtl1.namcfper as dtl1_name,

pdtl2.namcfper as dtl2_name

FROM foundation.cfcol c

JOIN foundation.cfins i ON c.inscfcol = i.codcfins

JOIN foundation.cfexp e ON c.expcfcol = e.namcfexp

LEFT JOIN foundation.expanded_roles ertl

JOIN foundation.cfper ptl on ertl.person_id = ptl.pidcfper

ON ertl.entity1_id = c.expcfcol and ertl.entity1_type = 'EXPERIMENT'

AND ertl.entity2_id = c.inscfcol and ertl.entity2_type = 'INSTITUTE' and ertl.role_type = 'TL'

LEFT JOIN foundation.expanded_roles erdtl1

JOIN foundation.cfper pdtl1 on erdtl1.person_id = pdtl1.pidcfper

ON erdtl1.entity1_id = c.expcfcol and erdtl1.entity1_type = 'EXPERIMENT'

AND erdtl1.entity2_id = c.inscfcol and erdtl1.entity2_type = 'INSTITUTE' and erdtl1.role_type = 'DTL' and erdtl1.priority = 100

LEFT JOIN foundation.expanded_roles erdtl2

JOIN foundation.cfper pdtl2 on erdtl2.person_id = pdtl2.pidcfper

ON erdtl2.entity1_id = c.expcfcol and erdtl2.entity1_type = 'EXPERIMENT'

AND erdtl2.entity2_id = c.inscfcol and erdtl2.entity2_type = 'INSTITUTE' and erdtl2.role_type = 'DTL' and erdtl2.priority = 50

WHERE e.namcfexp = :exp

Now we have a bit of a problem! The database must access the expanded role and person tables 3 times, once for each possible role. This can be especially bad if we don’t have the where condition filtering on a specific experiment.

Fortunately there is another way. The pivot!

SELECT * FROM (

SELECT c.expcfcol as experiment_id,

e.txtcfexp as experiment_name,

c.inscfcol as institute_id,

i.or1cfins as institute_name,

i.placfins as institute_place,

p.namcfper as name,

case

when er.role_type = 'TL' then 'TL'

when er.role_type = 'DTL' and er.priority = 100 then 'DTL1'

when er.role_type = 'TL' and er.priority = 50 then 'DTL2'

end role_key

FROM foundation.cfcol c

JOIN foundation.cfins i ON c.inscfcol = i.codcfins

JOIN foundation.cfexp e ON c.expcfcol = e.namcfexp

LEFT JOIN foundation.expanded_roles er

JOIN foundation.cfper p on er.person_id = p.pidcfper

on er.entity1_id = c.expcfcol and er.entity1_type = 'EXPERIMENT'

AND er.entity2_id = c.inscfcol and er.entity2_type = 'INSTITUTE'

AND er.role_type in ('TL', 'DTL')

)

PIVOT (

max(name) as name

for role_key in ('TL' as teamlead, 'DTL1' as dtl1, 'DTL2' as dtl2, null as none)

)

WHERE experiment_name = :exp

So what’s going on? The pivot query consists on an inner part that contains the query returning multiple rows per collaboration (one for each person), plus a synthetic key we are using for the pivot. This key tells us what sort of row we have. In our case, each row is either a team lead (TL), the first deputy team lead (DTL1) or the second (DTL2). In other use cases you might use department or country as a pivot key, without the need for the synthetic value.

After the PIVOT keyword we list the measures to denormalise. Here we only want the person’s name, but we could also include other attributes of the person (e.g. first name). We must use an aggregate function to select the value even though we only expect one result per pivot key. You might have done something similar when using a group by statement, and in fact the PIVOT can be achieved with some clever use of decodes and aggregate functions in a group by statement instead of the pivot clause.

Any field in the original select query not referenced as a measure or key will become a grouping column. So be careful not to select unique identifiers in the select that aren’t referenced in the pivot clause. For example, including p.pidcfper in the select statement above would result in multiple rows per collaboration being returned, instead of just 1 that we are aiming for.

Our query looks both more complicated and yet simpler at the same time. There are no messy repeating joins, but we have a new syntax that we might not be familiar with (unless you’ve read this post!).

Performance

And what about performance? There is no additional data access necessary for the pivot but there is extra processing by the dbms to convert the rows in to columns (which is where the name pivot comes from, the rows are pivoted to columns). Is the overhead worth it?

Foundation

The aim in using the pivot is that we reduce data access at the cost of extra processing with the hope that computation is faster than disk access and we end up with a net benefit. When testing with the example foundation queries, the results were surprising.

The example queries are well structured “simple” queries with a consisting of joins based on foreign key relationships. The dbms is extremely good at handling these sorts of queries and surprisingly, there is little difference between the 2 query approaches. The 3 joins query is actually almost twice as fast when selecting results for a specific experiment and very slightly slower when selecting all rows.

-- statement 1 = 3 joins

-- statement 2 = pivot

-- each query executed 2 times, with 5 runs

-- where experiment_name = ? order by institute_name

Run 1, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:00.268184000

Run 1, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:01.186459000

Run 2, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:00.050562000

Run 2, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:00.091722000

Run 3, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:00.048616000

Run 3, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:00.095397000

Run 4, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:00.042662000

Run 4, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:00.085043000

Run 5, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:00.054934000

Run 5, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:00.084433000

-- order by institute_name

Run 1, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:01.711240000

Run 1, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:00.247038000

Run 2, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:00.220213000

Run 2, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:00.209251000

Run 3, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:00.224166000

Run 3, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:00.218305000

Run 4, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:00.222989000

Run 4, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:00.211690000

Run 5, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:00.226773000

Run 5, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:00.206624000

Greybook

The real world is not so simple. There are edge cases and additional requirements that mean business logic creeps in to the query and underlying views which can dramatically change the performance. The real greybook query that started this investigation has the same general structure and accesses the same foundation tables as the example query, but includes additional logic and extra tables which results in a very different performance profile.

In the real example, the pivot query is an order of magnitude faster than the 3 joins when selecting for a single experiment and 2-3 times faster when selecting all rows.

-- statement 1 = 3 joins

-- statement 2 = pivot

-- each query executed 2 times, with 5 runs

-- where experiment_name = ? order by institute_name

Run 1, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:41.159630000

Run 1, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:03.277204000

Run 2, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:36.383310000

Run 2, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:03.263769000

Run 3, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:34.072796000

Run 3, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:03.084284000

Run 4, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:33.952187000

Run 4, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:03.104582000

Run 5, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:34.135544000

Run 5, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:03.311002000

-- order by institute_name

Run 1, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:45.023896000

Run 1, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:16.886233000

Run 2, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:40.786438000

Run 2, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:14.260805000

Run 3, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:37.057331000

Run 3, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:16.684773000

Run 4, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:36.982896000

Run 4, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:14.406066000

Run 5, Statement 1 : +000000000 00:00:37.084015000

Run 5, Statement 2 : +000000000 00:00:14.264781000

Conclusion

Maybe to be expected, there is no clear winner in terms of performance. While in theory the pivot query should be faster because it involves less data access, in practice, with a well structured schema with clearly defined relations the data access cost can be minimal compared to the extra overhead. The biggest take away for me is that each little bit of business logic that creeps in to a query, instead of being modeled by the data structure, adds up to have a significant negative impact on performance. A clean schema beats a fancy query.

Notes and Gotchas

The values of the pivot key must be known at query time. You may see documentation that mentions you can use a sub query to select the key values, but this only works if you use the xml option…and then your result set is XML. You might find that useful but I haven’t.

These queries have a fatal assumption. It assumes there is only one TL, and one DTL for priority 100 and 50. Since our schema does not enforce this, if the data does not obey this convention we will get incorrect results because of the aggregate function and joins. Max is only safe to use when there is a single result. To fix this, we could use a row_number window function to give each person with the same role a rank based on the role priority and use the row number in the case statement instead of priority.

Resources

- https://www.oracle.com/technical-resources/articles/database/sql-11g-pivot.html

- https://docs.oracle.com/cd/B28359_01/server.111/b28286/statements_10002.htm#SQLRF01702

- https://www.oracletutorial.com/oracle-basics/oracle-pivot/

- https://blog.jooq.org/tag/pivot/

- https://blog.jooq.org/how-to-benchmark-alternative-sql-queries-to-find-the-fastest-query/